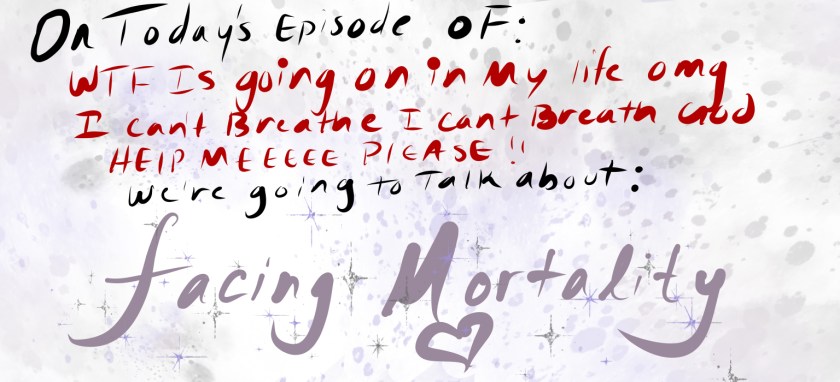

I fell asleep at 8pm last night and woke up at 5 this morning and so let’s talk about death.

I read this essay called Learning How to Die in the Anthropocene by Roy Scranton in the book Modern Ethics in 77 Arguments. If you’re a philosophy buff like me, if you took a lot of classes in undergraduate college on the subject and found that you talked often about the older guys and not so much about the people today, then this is the book for you. I will say some of the people today are lacking in their creative abilities and misunderstanding a lot of basic philosophical concepts, but I guess that’s just how we move with the time.

How to Die in the Anthropocene (our new era today), though, is well above some of the other essays I’ve read so far in this book. It talks about facing one’s death in light of climate change, in light of war, in light of being human and succumbing to our ultimate end. Scranton challenges that a bunch of philosophers sitting around and talking about life doesn’t make changes, BUT that the Anthropocene may indeed be the most philosophical of ages in that it’s requiring we question what it means to live, what does being human mean, and, most importantly, what do our lives mean in the face of death? He says, “What does one life mean in the face of species death or the collapse of global civilization? How do we make meaningful choices in the shadow of our inevitable end? . . . we have entered humanity’s most philosophical age–for this is precisely the problem of the Anthropocene. The rub is that now we have to learn how to die not as individuals, but as civilization.”

He describes his time in Iraq and how he faced death everyday. Yamamoto Tsunetomo’s Hagakure, a samurai manual, provided some solace. It said we should “meditate on inevitable death” daily. And so Scranton did so, imaging each day that he’d be blown up or shot or killed in some other war-torn, horrific sense, and he’d tell himself he didn’t need to worry because he was already dead. What mattered, then, was helping others come back alive. Tsunetomo says, “If by setting one’s heart right every morning and evening, one is able to live as though his body were already dead. . . He gains freedom in the Way.”

In the end, we realize that we are already dead. Each day is a new death for us in that every moment is something new, the next moment new still. We are indeed living death. Scranton doesn’t focus on what we need to do to save ourselves or our planet, he focuses on the fact that we’re already dead and that instead we should focus on adapting to this new way of life; “we can continue acting as if tomorrow will be just like yesterday, growing less and less prepared for each new disaster . . . or we can learn to see each day as the death of what came before, freeing ourselves to deal with whatever problems the present offers without attachment or fear.”

That is learning how to die.

We can apply this to physical life just the same as Scranton did. When someone passes, they leave behind what has come before (life) and if they move on to something, each moment will start anew again, as there is nothing that doesn’t come with something; if something came alone, there would be no such thing as nothing, and visa-versa. If we didn’t have death, there would be no life, quite literally, and so to those wondering whether living infinitely is possible, it’s not. You wouldn’t be alive if you can’t die. You couldn’t even “be” because there is no chance for you to “not be.” Sorry to burst your bubble.

I would argue that in the face of death our life means exactly what it’s meant to mean: we are here, shortly, and then we are not, and that goes the same for the bee that stung my foot, for the plants I sniffed as a child, for my first cat who died peacefully on the kitchen floor. We aren’t here to make a purpose on earth, we’re here to die. And the sooner you’re okay with that, the sooner life will be enjoyable.

Death hurts. I would go so far as to say it’s the most hollow, defeating, crushing feeling I’ve ever felt, to have someone pass on without either of you ready for that. But it doesn’t have to be. They have not only graduated from life, they’ve completed their purpose.

We can’t know if anything is next, we’re almost purposefully physically limited from ever knowing something like that. All we can know is that we will all complete the same end-goal and we should find celebration and happiness in what people do here and in their graduation.

This isn’t a somber topic. Rejoice.

Until next time.

Don’t forget to hit that follow button and join me over on Instagram @alilivesagain or on Twitter @Thephilopsychotic.